The real issue isn’t synchronous vs asynchronous learning

Most debates about synchronous versus asynchronous learning in healthcare start in the wrong place. The problem usually isn’t that educators chose the wrong format. It’s that formats get treated as strategies, rather than tools that serve different learning purposes.

In healthcare and teacher education alike, learning often gets designed around availability instead of outcomes. If time appears on the calendar, a live session gets scheduled. If schedules clash, content moves online and becomes “asynchronous.” However, neither decision says much about how people actually learn, reflect, or change their practice.

This becomes especially visible in practice-based education. Learners are expected to develop judgment, communication skills, and professional identity while juggling placements, workload, and emotional pressure. In that context, more “live” time does not automatically mean better learning. At the same time, more flexibility does not guarantee depth or engagement.

Research following the rapid shift during COVID-19 made this clear. Studies consistently showed that both synchronous and asynchronous approaches can support learning, but they do so in different ways. Alzahrani et al. observed that students valued synchronous learning for interaction, while asynchronous learning supported time management and flexibility, particularly for learners balancing study with practice. The insight here is not about preference. It’s about fit.

So instead of asking which format is better, a more useful question is this: what problem is this learning activity meant to solve? Once that becomes clear, the choice between synchronous and asynchronous learning often becomes obvious.

When does live interaction genuinely earns its place?

Live, synchronous learning earns its value when learning depends on shared sense-making rather than information transfer. Real-time interaction matters most when learners need to test reasoning, surface assumptions, or calibrate their thinking against others.

In healthcare education, this shows up clearly in areas like clinical reasoning, ethics, communication skills, and interprofessional collaboration. Mao et al. describe synchronous learning as enabling “direct interaction between teachers and students,” which helps clarify complex or nuanced topics and reduce misunderstanding. The value here lies in dialogue, not delivery.

The same pattern applies in teacher education. Live discussion supports classroom management scenarios, ethical dilemmas, or feedback conversations where tone, timing, and perspective matter. In these moments, immediacy allows learners to ask questions they didn’t know they had and to see how others interpret the same situation differently.

However, live interaction comes at a cost. It requires coordination, sustained attention, and emotional presence. Alzahrani et al. found that while learners experienced synchronous sessions as more interactive, they also experienced greater pressure on time and scheduling compared to asynchronous formats. This means live time should be used deliberately, not routinely.

Synchronous learning adds the most value when alignment, clarification, or social calibration is the goal. When it’s used simply because it feels more “real,” it often crowds out reflection and overloads both learners and educators. Recognising when live interaction truly earns its place is one of the most important design skills in modern healthcare and teacher education.

When does stepping back improve learning more than being present?

In practice-based education, some of the most meaningful learning happens after the moment has passed. Asynchronous learning earns its place when learners need time to think, revisit experience, and connect feedback to future action. This is less about convenience and more about cognitive space.

Recent research supports this shift. A comparative study evaluating synchronous and asynchronous online teaching in medical education found that both formats improved learning outcomes and student satisfaction, with no significant difference between them. The key difference was not performance, but how learners engaged. Asynchronous formats reduced pressure and allowed learners to process information at their own pace, which supports deeper understanding rather than rapid response.

This matters for outcomes such as clinical reasoning, communication, and professional judgment. Reflection after action allows learners to identify patterns, recognise uncertainty, and integrate feedback more meaningfully. Research on remote asynchronous training and feedback shows that delayed, structured feedback still leads to performance improvement when learners can review their own recordings and return to feedback multiple times.

Asynchronous learning also strengthens assessment quality. Written reflections, recorded artefacts, and documented feedback create traceable evidence that supports fair and defensible evaluation. This is especially important in healthcare and teacher education, where assessment decisions must withstand scrutiny. Videolab’s overview of reflective practice in healthcare training shows how structured reflection turns asynchronous learning into an active and accountable process.

Stepping back, in this context, is not disengagement. It is often where learning consolidates and professional identity begins to form.

The balance between synchronous and asynchronous learning

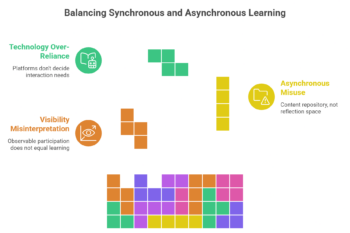

Despite growing evidence, many education programs still struggle to balance synchronous and asynchronous learning effectively. The issue is rarely a lack of tools. Instead, it stems from how institutions interpret visibility, engagement, and control.

Live sessions feel productive because participation is observable. Attendance can be tracked, interaction can be seen, and teaching feels tangible. However, research consistently shows that visibility does not equal learning. A study comparing synchronous and asynchronous formats in nursing education found no significant difference in learning outcomes, even for complex domains such as ethical decision-making. This challenges the assumption that real-time interaction is inherently superior.

At the same time, asynchronous learning often gets misused. Instead of being designed for reflection and consolidation, it becomes a repository for content. When that happens, motivation drops and learning becomes superficial. Studies in healthcare education show that learner characteristics such as self-regulation and instructional design quality predict outcomes more strongly than delivery mode.

Another common misjudgment is treating technology as a substitute for pedagogy. Platforms enable scale, but they do not decide when interaction or reflection is needed. In healthcare education, this creates real risks. Overusing synchronous sessions increases cognitive and scheduling load, while poorly designed asynchronous learning undermines feedback and assessment defensibility.

Programs that design learning around purpose rather than format avoid these traps. They use synchronous learning sparingly for alignment and sense-making, and rning deliberatelyasynchronous lea for reflection, documentation, and growth. This shift from format-driven to intention-driven design is what separates effective programs from merely busy ones.

A design rule educators can actually use

Once you stop framing synchronous and asynchronous learning as opposites, design decisions become much easier. Instead of asking which format to choose, it helps to ask what kind of learning you want to enable at that moment.

A useful rule of thumb in healthcare and teacher education is to align format with intent. When the goal is shared understanding or alignment, synchronous learning adds value. Live discussion helps surface assumptions, calibrate expectations, and build a common frame of reference. This is why case discussions, ethical dilemmas, and communication exercises often work best in real time.

When the goal is insight or consolidation, asynchronous learning usually performs better. Learners benefit from stepping back, revisiting experience, and reflecting without time pressure. Research comparing synchronous and asynchronous approaches consistently shows no significant differences in learning outcomes when design is intentional, which suggests that reflection and pacing matter as much as interaction.

When the goal is accountability or defensible assessment, asynchronous workflows become essential. Recorded artefacts, written reflections, and documented feedback provide traceability, which supports fair evaluation and accreditation. This principle underpins many feedback models in healthcare education, where assessment decisions must remain transparent. Our overview of feedback models in healthcare training illustrates how structured, documented feedback strengthens both learning and governance.

A practical checklist for choosing between synchronous and asynchronous learning

Before scheduling a session or designing a module, one question helps prevent misalignment: What should learners be able to do differently after this activity?

If the answer involves insight, judgment, or transfer, asynchronous components deserve as much attention as live ones. The table below helps shift the conversation away from formats and toward intent.

In healthcare education, this distinction becomes clear in day-to-day scenarios. Take a case discussion around diagnostic uncertainty. When learners need to compare reasoning paths, challenge assumptions, and hear how others interpret the same information, synchronous learning earns its place. Real-time dialogue allows misunderstandings to surface quickly and helps groups align on how decisions get made. In these situations, the value does not come from content delivery but from shared sense-making.

By contrast, consider learning that follows performance, such as reviewing a recorded patient consultation or reflecting on a clinical handover. Here, asynchronous learning often leads to better outcomes. Learners benefit from stepping back, revisiting the interaction, and connecting feedback to their own thinking without the pressure to respond immediately. This is especially important for communication skills, where insight often emerges after emotions settle and context becomes clearer.

| Design need | Synchronous learning works best when you need to | Asynchronous learning works best when you need to |

|---|---|---|

| Learning intent | Build shared understanding and align perspectives | Support reflection, consolidation, and sense-making |

| Type of engagement | Real-time dialogue and immediate interaction | Thoughtful, self-paced engagement over time |

| Cognitive demand | Work through ambiguity, disagreement, or ethical tension | Reduce time pressure and allow deeper processing |

| Skill focus | Practice communication, discussion, or interaction live | Review performance, analyse decisions, and refine skills |

| Learner experience | Create social presence and group calibration | Give learners space to revisit material and feedback |

| Time and scheduling | Coordinate learners at the same moment | Fit learning around busy or unpredictable schedules |

| Feedback approach | Provide immediate clarification and coaching | Offer structured, documented feedback that can be revisited |

| Assessment needs | Explore understanding in the moment | Create traceable evidence for assessment and progression |

| Best use in practice | Case discussions, debriefings, alignment sessions | Reflection, portfolios, follow-up work, longitudinal learning |

Scheduling and cognitive load also play a role. Healthcare learners frequently balance education with clinical duties, making it difficult to sustain attention during frequent live sessions. Asynchronous learning absorbs this pressure by allowing engagement at moments when learners are cognitively ready. This does not reduce accountability. On the contrary, structured asynchronous activities such as written reflections, annotated video review, or feedback logs create traceable evidence of learning that supports fair assessment and progression decisions.

Blended approaches often work best when learning goals span understanding and application. For example, a live simulation debrief can help learners align on expectations and identify key moments. Follow-up asynchronous reflection then allows individuals to analyse their own performance, revisit feedback, and track improvement over time. This sequence respects both the social and reflective dimensions of learning.

Using the table as a design check makes these choices more intentional. When educators match learning mode to purpose, synchronous and asynchronous learning stop competing for attention. Instead, they work together to support deeper understanding, sustained engagement, and learning that holds up beyond the classroom or clinical setting.

Designing learning with intention, not habit

The difference between synchronous and asynchronous learning is not a technical distinction. It is a design decision that shapes how people think, reflect, and develop professional judgment. Problems arise when formats are chosen by habit, availability, or institutional default rather than by purpose.

Live interaction earns its place when alignment, dialogue, and shared understanding matter. Stepping back earns its place when insight, consolidation, and accountability matter. Learning improves when both are used deliberately, not interchangeably.

Well-designed asynchronous learning is no longer optional in modern education. It supports reflection, documentation, and continuity in ways live sessions cannot replace. At the same time, synchronous learning remains essential when meaning is co-constructed rather than consumed.

The most effective programs do not ask which format to choose. They ask what kind of learning they want to enable, then design accordingly. When that question guides decisions, synchronous and asynchronous learning stop competing and start working together.