Updated: 2 April, 2024

Key takeaways:

- Properly delivering bad news is crucial for maintaining the quality of care and avoiding problems that can arise from emotional reactions to the messenger and the information.

- Doctors face fears such as being blamed, lacking training in communication skills, suppressing emotions, and not knowing all the answers when delivering bad news to patients. Addressing these fears through training can improve the delivery process.

- Patients’ reactions to bad news can be unpredictable, but it is now recognised that patients have a right to know and prefer honest and empathetic disclosure of bad news.

- Models like Fine’s, SPIKES, and ABCDE provide structured approaches to delivering bad news, covering preparation, assessing perception, obtaining patient invitations, sharing information, addressing emotions, and formulating a strategy.

Introduction

“Don’t shoot the messenger!” they say, but many people do. Especially when the message is badly delivered, the emotional reaction to the messenger, but also to the information, creates problems damaging the quality of care received. Fortunately, there is ample research about the best ways of delivering bad news to patients. In this article, we summarise some of the core ideas.

The delivery of bad news has always been a sensitive topic to discuss, but it has not always been approached in the same way throughout the years. In the late 1970s and 1980s, many characteristics related to the doctor’s profession were assumed to be innate, such as communication skills and the ability to feel or sense what the patient is experiencing (Buckman 2002). However, these beliefs were erroneous. All medical education now also focuses on soft skills, empathy, and communication skills. Delivering bad news is taught and learned. Let us explore how.

Why is delivering bad news so difficult?

What is “bad news” in healthcare? Bad news is “any news that drastically and negatively alters the patient’s view of her or his future” (Buckman, 1984). Delivering bad news poses a difficult mission for two primary reasons: it challenges both the doctor and the patient. The doctor faces various obstacles, as discussed below, while the patient must receive a message that will significantly impact their future life. On the one hand, there are many problems that doctors are facing when the need for breaking bad news arises.

Some of these fears include:

- The fear of being blamed. Doctors often fear that the patient will tend to blame the person delivering the bad news. At the heart of this fear is the identification of the target for the blame. The level of simplicity in identifying the authority delivering the bad news is high when a doctor breaks bad news, it is… the doctor itself. (Buckman, 1984).

- The fear of the unknown and untaught. In the past, doctors weren’t trained enough in communication skills, nor in discussing a patient’s fatal disease with the patient itself. This lack of training and experience leads doctors to feel awkward in delicate situations such as breaking bad news, further encouraging them to avoid this type of situation. (Buckman, 1984)

- Fear of expressing emotions. Doctors have often been taught to suppress any panic in emergencies and to remain calm and composed. This has become part of the standard in many situations, leading to a need to relearn, as a deliberate effort, the manifestation of human empathy and sympathy. (Buckman, 1984)

- Fear of not knowing all the answers. Usually, the more senior a doctor is, the more comfortable he will be and the lesser self-confidence he will lose by saying “I don’t know”. And it might be the same for the listener; it is almost a universal law that one person must seem to have a big quantity of knowledge before being “allowed” to confess to not knowing it at all. However, when it comes to breaking bad news, knowing The Answer may not be as important as it seem to be. What the patient is really looking for is a doctor that can genuinely listen and is attentive. (Buckman, 1984)

Patients are unpredictable…

On the other side of the bad news, we find the patient, whose reaction to the news can be difficult to predict. Because such an announcement will affect the patient adversely, back in the old days doctors may have withheld the news. Hippocrates advised “concealing most things from the patient while you are attending to him. Give necessary orders with cheerfulness and serenity…revealing nothing of the patient’s future or present condition. For many patients…have taken a turn for the worse…by forecast of what is to come” (Hippocrates, 1923).

Nowadays the ethical consensus is that the patient has a right to know, and the doctor and obligation to inform. Numerous studies have shown that patients usually want honest and empathetic disclosure of a terminal diagnosis or other bad news. (Buckman, 1984). The results of this study lead us to the next point. Breaking bad news is emphasized as an important skill rather than an innate quality.. A skill that can be learnt.

Learning to Deliver Bad News

In the past, the focus in medical training placed more value on technical proficiency than on communication skills. Therefore, due to the lack of training in these skills, many physicians felt unprepared for the difficulty of breaking bad news. Consequently, this feeling of unpreparedness leads the physicians to be increasingly uncertain and uncomfortable. The observed consequence is a disengagement of physicians from situations in which they have to deliver bad news. Moreover, like Dr. Vandekieft, assistant director of the Palliative Care Education and Research Program at Michigan State University, said: “A physician’s attitude and communication skills play a crucial role in how well patients cope when they receive bad news” (Vandekieft, 1976).

difficulty of breaking bad news. Consequently, this feeling of unpreparedness leads the physicians to be increasingly uncertain and uncomfortable. The observed consequence is a disengagement of physicians from situations in which they have to deliver bad news. Moreover, like Dr. Vandekieft, assistant director of the Palliative Care Education and Research Program at Michigan State University, said: “A physician’s attitude and communication skills play a crucial role in how well patients cope when they receive bad news” (Vandekieft, 1976).

These cumulative effects bring us to one obvious conclusion: breaking bad news is an important skill to have. Learning and developing this specific communication skills will make the physician less uncomfortable when announcing bad news. This in turn increases the satisfaction of the patient and his or her family (Ellis & Tattershal, 1999). Without much surprise, multiple studies have demonstrated that focused educational initiatives ameliorate student skills in delivering bad news (Cushing et Al. 1995, Garg et Al., 1997 and Vetto et Al., 1999).

How to Deliver Bad News?

Over time, experts have created different models for delivering bad news, and this section discusses three major models.

How to use Fine’s Model to Deliver Bad News:

Fine’s model: Fine elaborated a protocol with five different phases.

1) The first phase is called preparation and involves all the activities surrounding the delivering of bad news. It involves establishing appropriate space, being sensitive to the patient’s needs, cultural and religious values and being goal-specific.

2) The information acquisition stage. It consists of asking the patient what he or she already knows, what he or she believes and is willing to know.

3) Is the information sharing phase. It includes agenda re-evaluation and teaching.

4) The penultimate stage. This is the information reception and allows for the clarification of any miscommunication, misunderstanding and the careful handling of disagreements.

5) Finally, the last phase entails identifying and acknowledging the patient’s response to the news and closing the interaction (Fine, 1991).

How to use SPIKES model to deliver bad news:

SPIKES: Baile et al proposed a comprehensive model called SPIKES. This protocol is divided into six different steps to follow (Baile et al, 2000).

1) Setting up the interview. In order for the interview to be successful and have a chance to meet its goals, the doctor must arrange for privacy, involve of a significant other (like a family member for instance), sit down and make connection with the patient, as well as manage time constraints and interruptions.

2) Involves assessing the patient’s Perception. It is very important to ask open-ended questions before touching on medical findings to have a clear grasp of how the patient perceives the medical situation and consequently adapt the bad news announcement to the patient’s understanding.

3) Third, the bad news deliverer needs to obtain the patient’s Invitation. Every patient is different in his or her desire for information disclosure, and a clear expression of such a desire will reduce the doctor’s anxiety.

4) The actual Knowledge and information sharing to the patient. It is important to warn the patient that bad news is coming in order to lessen the shock as much as possible and to ease information processing. Use of understandable non-technical vocabulary, avoidance of excessive bluntness, and the sharing of information in small chunks.

5) Addressing the patient’s Emotions with empathetic responses. As the patient’s response varies from patient to patient, this step is the most complicated one. To address the emotion, empathetic statements can be brought forward. If the emotion is not clear, exploratory questions can be used.

6) The ultimate steps consists of formulating a Strategy and making a Summary. In this part, it is important that the patient feels involved into the decision making process involving the treatment(s).

How to Deliver Bad News using the ABCDE model:

Another comprehensive model that can be used to deliver bad news more compassionately and effectively. It was developed by Rabow and McPhee under the name ABCDE (VandeKieft 1975-8). This model includes five steps.

1) Advance preparation. This includes learning about what the patient already knows, arrange for a good time and setting, prepare a possible script and prepare for emotions.

2) Build a therapeutic environment and relationship. In other words, the place should be quiet and private and the doctor should sit close enough to touch if appropriate.

3) Communicate well. This means being direct, not using medical jargon, allowing for silence, etc.

4) Deal with the patient and family reactions. Listening actively, exploring and having empathy are crucial tasks during this phase.

5) Encouraging and validating emotions. During this step, future patient’s needs should be addressed based on the exploration of what the news means to the patient (Rabow, 1999)

What Methods to Use to Learn to Break Bad News?

Now we can clearly see that by learning general communication skills and utilising models like the ones described above, physicians can deliver bad news in a more comfortable manner, while patients and their relatives can receive it more appropriately. Moreover, there have been numerous investigations that revealed the benefits of focused educational interventions. And improving student and resident skills in such a domain.

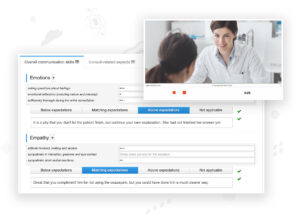

To develop such skills, medical schools and other faculties requiring this type of soft skill use Videolab as a powerful tool. Leading universities and medical centres across Europe utilise Videolab as the central platform for students. In many institutions, the training and the recording of delivering bad news is a common practice. Such as at the “Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh”, where there exists communication skills competition, focused on the delivery of bad news.

The training of bad news can be enhanced through Videolab in the following way. Trainees record videos and upload them on Videolab. They can then examine their performance, engaging in self-reflection by adding by adding fragment comments, symbols or general remarks. The delivery and reception of bad news vary depending on the individual. Feedback from peers and professors is a valuable instrument. This is valuable because it offers different perspectives and fostering open-mindedness to better prepare for future real situations. Moreover, professors are also able to upload specific videos related to breaking bad news for teaching purposes, and students are able to assess what to do and what not to do.

Conclusion

Everything is in place for the current and future healthcare professionals to be trained in the deliverance of bad news. Codific is here to help with the practical implementations. Let’s build a simple and safe digital future together.