Updated: 1 September, 2025

Their Role in Healthcare Training

In clinical education, understanding the distinction between self-awareness vs self-reflection is key to developing empathetic, skilled healthcare professionals. Although the terms are often used interchangeably, they serve different roles. As expectations for soft skills and adaptive expertise increase, clarifying the roles of self-awareness and self-reflection has become a cornerstone of effective healthcare training.

Self-awareness refers to the ability to recognize thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as they occur. Self-reflection, on the other hand, involves stepping back after an experience to analyze it critically and learn from it. Together, these skills support the goals of modern medical education: improving safety, reducing burnout, enhancing empathy, and fostering professional identity. When both are integrated into training programs, they provide a metacognitive framework that helps students become not just technically capable, but also emotionally intelligent and ethically grounded.

When educators treat these processes as identical, they risk overlooking essential opportunities to guide learners in real-time adjustment and long-term growth. Distinguishing and intentionally cultivating both can sharpen training strategies and strengthen clinical readiness.

Definitions and Core Differences

Self-awareness vs self-reflection differ in timing and function but are equally important in healthcare training. Self-awareness happens in the moment. It enables clinicians to notice emotional cues, internal reactions, or biases during a patient interaction. Ronald Epstein emphasized that mindful practitioners who tune into their emotional state make more ethical, effective decisions (Epstein, 1999). Goleman similarly noted that emotional intelligence begins with recognizing one’s feelings as they arise (Goleman, 1995). In medical education, this might look like a doctor noticing tension while delivering a diagnosis, and adjusting their tone or posture in real time.

Recent studies like the Reflective Mindfulness and Emotional Regulation Training (RMERT) show that structured training improves students’ ability to regulate emotions and stay composed under pressure (BMC Nursing, 2025).

Self-reflection, by contrast, is retrospective. Drawing from Dewey and Schön’s work, it involves reviewing experiences, often after uncertainty or emotional discomfort, to understand what happened and what could be improved (Schön, 1987). Donald Schön later expanded this into two main modes: reflection-in-action, which happens during a situation, and reflection-on-action, which occurs afterward. Mamede and Schmidt’s 5-factor model frames it as a cognitive strategy involving deliberate induction, deduction, hypothesis testing, openness, and meta-reasoning (Mamede & Schmidt, 2004).

These components are used in OSCE debriefs, video-based feedback, and clinical simulations, where learners analyze how they acted and what they might do differently next time. When practiced regularly, it builds deeper learning and supports long-term clinical judgment.

Key Differences Between Self-Awareness and Self-Reflection

Although interconnected, self-awareness and self-reflection operate differently and require separate teaching approaches. Each contributes to communication, decision-making, and professionalism, but in distinct ways. Understanding their differences helps educators design more effective training strategies, while allowing students to identify and improve their learning processes.

Here’s how they differ:

| Dimension | Self-Awareness | Self-Reflection |

|---|---|---|

| Timing | During the experience | After the experience |

| Trigger | Emotional or cognitive cue | Outcome uncertainty or discomfort |

| Cognitive Mode | Monitoring and noticing | Analyzing and evaluating |

| Intention | Self-regulation and responsiveness | Learning and improvement |

| Feedback | Internal, often unconscious | Structured, guided, or peer-based |

| Outcome | Real-time behavior adjustment | Informed future decision-making |

For example, a clinician delivering bad news might become aware of their tightening chest or elevated tone – this is self-awareness. Later, during a review of a video-recorded consultation, they may reflect on how their facial expressions or speech pacing affected the patient’s response. This is self-reflection. Both help in refining professional behavior, though from different angles.

Building awareness in real time creates richer material for later reflection, and regular reflection sharpens awareness for future interactions. Regular use of both forms a feedback loop: awareness feeds reflection, and reflection improves future awareness.

How They Work Together in Clinical Education

When paired, self-awareness and self-reflection enhance clinical learning in ways that neither can achieve alone.

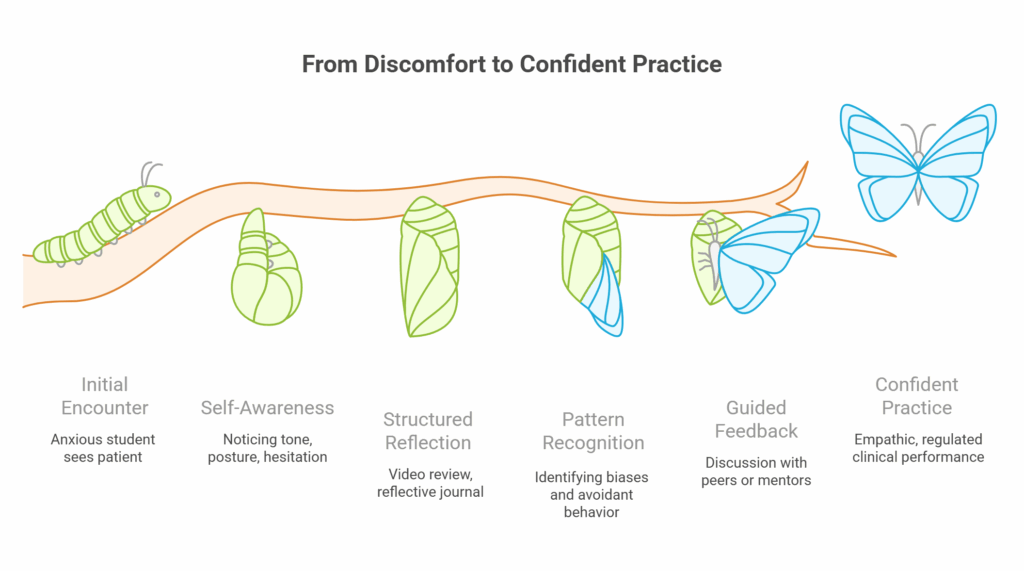

Undergraduate Training

During a consultation, for example, a student may notice rising anxiety as they approach a sensitive topic. That immediate recognition (self-awareness) can prompt a pause or change in approach. Later, through guided video review, the same student might observe that they avoided eye contact or rushed the conversation. This post-event analysis (self-reflection) helps connect behavior with intention and outcome.

In-the-moment video feedback encourages awareness of subtle cues like tone or posture. Structured debriefs then guide reflection using frameworks like Gibbs’ cycle. Together, these approaches turn isolated experiences into deliberate practice opportunities. By watching themselves or peers, students recognize habitual patterns, track improvements, and learn how to adjust with precision.

The RMERT study showed that integrating mindfulness and reflective tools helped learners regulate emotions in the moment and analyze their reactions post-event (BMC Nursing, 2025). A related meta-analysis on reflective practices in public health education found improvements in confidence, professional identity, and communication (Frontiers in Education, 2022).

By embedding both skills into everyday clinical training, educators foster more confident, emotionally intelligent practitioners ready for complex, human-centered care.

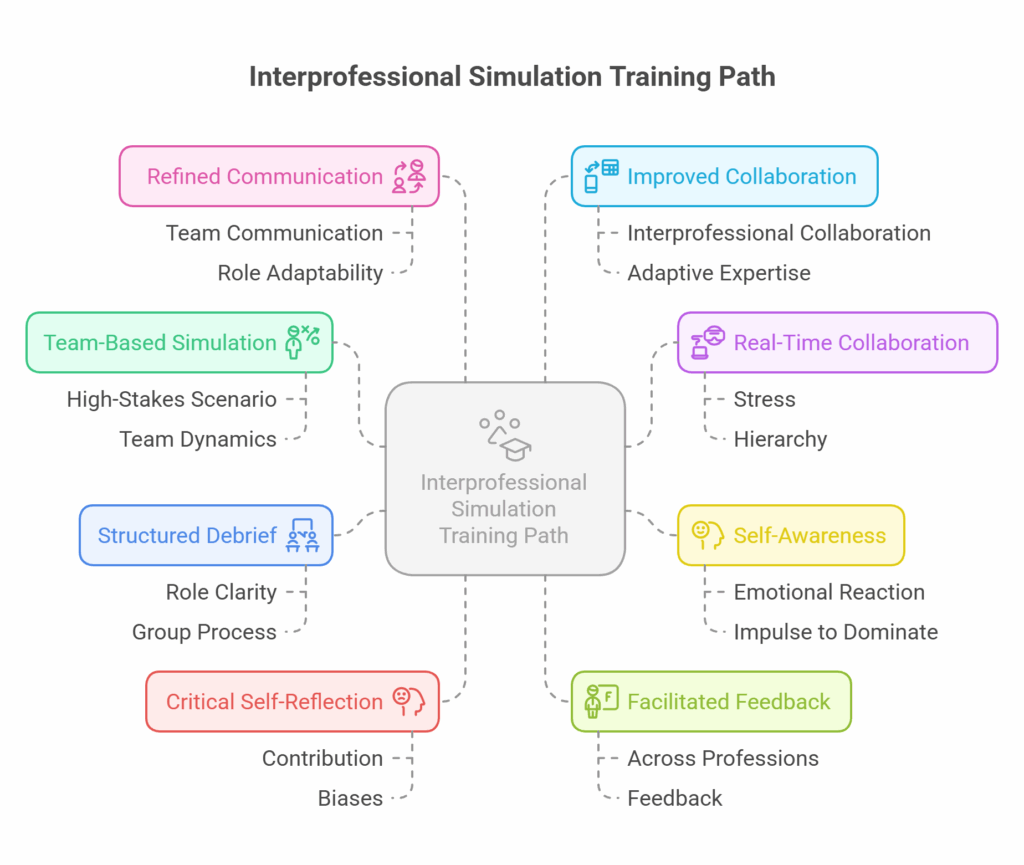

Interprofessional / Simulation Training

Nowhere is this integration more visible, and necessary, than in interprofessional education (IPE) and simulation training. These settings expose learners to high-stakes communication, teamwork under pressure, and real-world complexity, where both real-time responsiveness and post-event analysis are crucial.

In interprofessional scenarios, students from various disciplines must collaborate effectively while managing their own roles, assumptions, and emotional responses. Self-awareness enables learners to notice if they are dominating a conversation, reacting defensively, or missing a teammate’s perspective. This immediate recognition is essential for maintaining respectful collaboration, especially when hierarchies or discipline-specific tensions arise.

Self-reflection complements this by offering a space to analyze how those dynamics played out. After a simulation or team-based encounter, learners can review what went well, what triggered conflict or confusion, and how they contributed to team outcomes. This is where structured debriefing sessions, often facilitated by educators across professions, play a vital role in translating action into insight.

Simulation training also highlights the synergy between the two skills. For example, during a cardiac arrest scenario, a nursing student may become aware of their stress response – a spike in heart rate or hesitancy to speak up. That awareness can lead to better self-regulation in the moment. Later, reflective analysis may reveal patterns in decision-making, communication gaps, or moments of uncertainty. These insights feed forward into future scenarios, reinforcing adaptive expertise.

Why Medical Educators Should Distinguish and Cultivate Both

Treating self-awareness vs self-reflection as interchangeable can undermine the development of key clinical competencies. Educators who intentionally separate them can tailor teaching strategies to match specific learning goals – real-time adaptability versus deeper understanding.

Evidence shows that self-awareness helps prevent burnout and supports better decision-making. RMERT participants reported improved stress regulation and greater presence in patient interactions (BMC Nursing, 2025). Meanwhile, studies on reflective learning tie post-event reflection to long-term gains in empathy, communication, and clinical judgment (MacAskill et al., 2023).

These findings have clear implications for curriculum design. Self-awareness training is most effective when integrated into real-time learning such as live consultations, peer-to-peer simulations, or video-recorded OSCEs. By contrast, self-reflection benefits from structured debriefs, written assignments, or guided discussions. In both cases, feedback should include actionable, specific observations rather than general impressions. To learn more about different feedback models, check out this blog.

Practical Tools and Strategies

To effectively develop self-awareness and self-reflection, educators need structured, flexible tools. Reflective journaling offers a foundation for post-experience learning, especially when paired with established frameworks like Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle or Mezirow’s levels of reflexivity. Journals help students track emotions, intentions, and decisions over time.

Mindfulness exercises, practiced regularly, cultivate self-awareness in high-stakes environments. These routines help students recognize emotional shifts and manage their internal state during patient interactions.

Video-assisted tools offer a unique advantage because they can support both self-awareness and self-reflection. With tools like Videolab, can self-record clinical encounters, annotate their performance in real time, or review sessions later in guided debriefs. This flexibility allows students to track patterns in their communication, posture, and emotional responses while linking immediate behaviors to long-term improvement. Peer review and instructor-led analysis are also built into the platform, encouraging dialogic feedback and collective learning. Moreover, because Videolab is GDPR-compliant, students and faculty can safely store, annotate, and share sensitive footage without compromising ethical or legal standards.

By integrating tools that support both real-time monitoring and post-event analysis, clinical programs can move beyond theory to create practical, measurable growth in learners. This balance ensures students become not just skilled but self-aware and reflective practitioners.

Conclusion

Building the next generation of healthcare professionals requires more than teaching technical knowledge or procedural competence. It demands a focus on how clinicians think, feel, and respond – both in the moment and after the fact. Distinguishing self-awareness vs self-reflection gives educators the clarity to design more effective training and gives students the tools to grow with intention.

When both are embedded into simulation, interprofessional practice, and everyday clinical training, learners not only understand what to do, but why it matters and how to do it better next time. In a field that increasingly values adaptability, empathy, and collaboration, teaching these skills side by side is not just beneficial – it’s essential.