Updated: 2 January, 2026

Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) reshape how educators judge readiness for practice in health professions education. Rather than asking whether a learner can perform a task in theory or in simulation, educators now ask a more critical question: can this learner be trusted to carry out this task independently in real clinical environments?

Unlike Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs), which provide structured simulations, EPAs unfold in authentic clinical practice. The entrustment decision carries real consequences, for both the patient and the learner. This makes the assessment richer but also more complex: supervisors must evaluate not only technical performance, but also contextual judgment, communication, and reliability.

The challenge is that authentic clinical encounters are messy. Each case presents unique challenges, supervisors have limited opportunities for direct observation, and faculty often gather fragmented evidence to support entrustment decisions. This is where video-based EPAs, supported by platforms like Videolab, offer a transformative solution. They allow trainers to capture authentic performance, learners to revisit and reflect, and faculty teams to calibrate and document entrustment decisions in a transparent, defensible way.

The Stakes of Entrustment

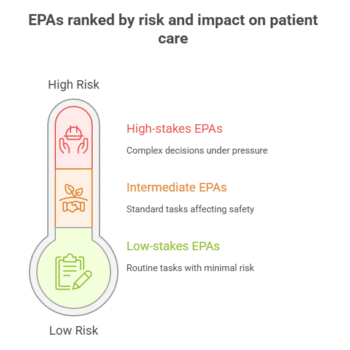

Not every EPA carries the same level of risk. Writing a discharge letter is important, but if a detail is missed, a supervisor can often correct it later. Compare this with leading a resuscitation team in the emergency department. A misjudgment there may cost a life. This is why educators often distinguish between low-, intermediate-, and high-stakes activities:

- Low-stakes EPAs: routine, low-risk activities such as documenting a consultation or updating a medication list.

- Intermediate EPAs: tasks like conducting a standard patient consultation or coordinating a ward handover. Mistakes here can affect safety and continuity of care.

- High-stakes EPAs: complex, emotionally or clinically demanding situations such as breaking bad news, leading interprofessional care, or making urgent decisions under pressure.

This spectrum is important because entrustment is not a single yes-or-no decision. It is a gradual progression. Learners must show reliability in low-stakes tasks before being considered for more demanding responsibilities. That progression requires evidence collected over time and across settings, not just one successful performance under observation.

Why Entrustment Is So Difficult in Practice

While educators agree that EPAs are powerful tools,the reality of implementing them is more complicated. Faculty consistently describe similar frustrations:

-

Each clinical encounter is unique. A learner might handle one patient perfectly and then stumble in another, making comparisons across students difficult.

-

No single supervisor sees everything. Entrustment often relies on ocassional observations or informal hallway conversations between colleagues.

-

Supervisors are pressed for time. Patient care takes priority, leaving little room for structured EPA assessment.

-

Documentation can feel endless. Recording entrustment decisions across multiple learners, across different EPAs, quickly overwhelms even the most motivated faculty.

-

Learners feel the pressure. Knowing that “every move counts” can create anxiety unless there is a parallel system for feedback and reflection.

These barriers explain why many institutions admire the idea of EPAs but struggle to make them systematic. Without better infrastructure, entrustment risks becoming arbitrary or inconsistent.

The Value of Video-Based EPAs in Assessment

Concerns about workload, calibration, and documentation are valid. But video provides a way forward.

- By recording authentic clinical encounters, educators can preserve the complexity of practice while making it available for later reflection and discussion.

- Asynchronous review means supervisor who cannot be present in the consultation room can still review the performance afterwards.

- Shared recordings help faculty align expectations and reduce variability.

- Integrated rubrics streamline documentation and reduce duplication.

- A learner who wonders how their communication came across can replay the moment and self-reflect with fresh eyes.

- The transparency of video portfolios removes the mystery around entrustment decisions. They can see the evidence, understand the reasoning, and track their own progress across time.

Platforms like Videolab make this feasible without compromising security. Our system encrypts recordings and deletes them from the device immediately after upload, eliminating the risk of a lost phone or misplaced file and leaving no data behind. This system ensures GDPR and HIPAA compliance while still making it possible to use authentic patient encounters for evaluation and self-reflection.

Implementing Video-Based EPAs Step by Step

Introducing video into EPA assessment is best done gradually:

-

Define the activities: Choose 3–5 core activities that matter most for early entrustment. Consultations, handovers, and informed consent discussions are good starting points.

-

Design structured rubrics: Adapt existing entrustment scales to your context. Ensure the forms capture levels of supervision, from “direct observation” to “independent practice.”

-

Secure recording workflows: Use Videolab Recorder Apps or CloudControl to capture encounters. Ensure consent processes are standardized and embedded in training.

-

Foster self-reflection: Encourage learners to watch and annotate their own recordings before supervisors comment. This builds self-regulation and makes feedback conversations more meaningful.

-

Layer in feedback: Invite peers, supervisors, and where possible, interprofessional colleagues to add fragment-specific feedback. The diversity of perspectives enriches learning and reduces bias.

-

Calibrate faculty: Review the same recording in small faculty groups to align standards. This minimizes assessor variability and builds confidence in decisions..

-

Build longitudinal portfolios: Aggregate recordings, reflections, and feedback into a learner portfolio. Use this portfolio as the basis for entrustment decisions, rather than one-off observations.

This roadmap ensures that video-based EPAs are not seen as surveillance or additional bureaucracy, but as a structured process that strengthens both learning and fairness.

Sample EPA: Leading an Interprofessional Handover

EPA Title: Conducting and Leading an Interprofessional Patient Handover

Description: The learner leads a structured handover involving at least two other health professionals (e.g., nurse, physiotherapist, pharmacist). The learner is expected to summarize the patient’s clinical status, integrate perspectives from different team members, and ensure continuity of care. This EPA focuses on clarity, inclusivity, and respect for professional contributions.

Expected Behaviors:

Organizes and prioritizes clinical information logically.

Invites input from different professionals and acknowledges their contributions.

Uses language that is clear, jargon-free, and understandable across disciplines.

Demonstrates respect, active listening, and responsiveness to team concerns.

Ensures that next steps and responsibilities are agreed upon and clearly documented.

Entrustment Level

Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4 Level 5 Description Requires direct observation Needs support in structuring the handover

Struggles to integrate perspectives or misses key contributions from other professionals

Can conduct a handover but needs prompting to invite contributions from others

May overlook important non-medical aspects such as nursing or rehabilitation concerns

Supervisor frequently intervenes to clarify or reorganize information

Leads the handover with adequate structure

Integrates most professional perspectives, though some omissions remain

Requires minimal correction; supervisor is present but rarely intervenes

Consistently organizes information clearly and invites interprofessional input

Demonstrates respect and inclusivity in communication

Anticipates questions from colleagues and addresses them proactively

Supervisor trusts the learner to lead handovers independently, intervening only if problems are reported

Functions as a reliable leader in interprofessional handovers

Integrates perspectives fluidly, balancing clinical, nursing, psychosocial, and rehabilitation aspects

Serves as a role model for peers and junior learners

Supervisor seeks feedback from the team rather than observing directly

From Simulation to Trust

Video bridges the two worlds. The same platform that records OSCEs also captures real patient encounters, creating a continuous assessment journey. Learners demonstrate competence in simulation and then test it in practice, earning trust through repeated, authentic performance.

Ultimately, EPAs are not just a new assessment tool. They are a cultural shift in how we think about readiness for practice. They move us from testing isolated skills to judging trustworthiness in context.

Video-based EPAs make this cultural shift workable. They give learners opportunities for reflection, practice for mastery, and feedback from multiple professionals. They give supervisors transparent evidence for defensible decisions. And they give patients confidence that those entrusted with their care are not just competent on paper but trustworthy in practice.